Odd Man Out - Carol Reed's Other Masterpiece

- Brian Watt

- Mar 25, 2018

- 6 min read

Updated: Jun 7, 2018

Although I fancy myself a film buff and have a fairly extensive film library of DVDs, Blu-rays and books on film, there are many films that I haven’t seen and older films, especially silent films now being preserved and made available in Blu-ray format thanks to advances in digital restoration technology. An example of a film that I’ve often heard about but never have gotten around to watching is Carol Reed’s Odd Man Out (James Mason, Cyril Cusack, Robert Newton, Kathleen Ryan)…until last night. I’m a big fan of Reed’s postwar films The Third Man (Joseph Cotten, Orson Welles, Trevor Howard), and The Fallen Idol (Ralph Richardson in arguably his best performance), both collaborations with novelist Graham Greene based on his stories. Reed, later in his career, was also called upon to direct the film of the stage musical Oliver (1968), one of the best musical films made of any period which garnered six Oscars including Best Picture and Best Director for Carol Reed.

Odd Man Out (1947) was the first of Reed’s postwar films based on a contemporary novel by F.L. Green on the ‘troubles’ in Northern Ireland with the IRA referred to in the film as the “organization”. The novel (which I have not read), is described in one of the Criterion Collection Blu-ray documentaries included in the Blu-ray release and elsewhere on the Internet, is more of an overt condemnation of IRA tactics than Reed’s film is and even though the novelist collaborated on the screenplay, Reed made the film much more complex and ambiguous, making the protagonist, Johnny McQueen (James Mason) the leader of an IRA gang a much more forlorn, conflicted and sympathetic character.

The film doesn’t reference real historical events or characters of the Northern Ireland conflict between the minority Catholic populace and the dominant Protestants. In fact, the film never overtly states that the story is set in Belfast, though it begins with an aerial shot from an airplane over Belfast and some of the daylight street scenes are shot there but other scenes in the film were shot at the D&P Studio in Buckinghamshire England, and in London’s Broadway Market area doubling for parts of Belfast. The urban setting, like the divided postwar Berlin in Reed’s later work, The Third Man, is shown for the most part in a dark, stylized way heavily influenced by German expressionist films and some of Fritz Lang’s work (M, The Testament of Dr. Mabuse), French poetic realism (Pépé le moko, The Lower Depths, etc.) and American film noir emerging around the same time – though it probably can be argued that Reed and cinematographer Robert Krasker were as influential on American film noir directors and cinematographers as they were on them.

IRA gang leader Johnny McQueen (James Mason), in making his escape after his gang has robbed a factory mill office, gets dizzy and disoriented and tangles on the pavement with an armed man from the mill. As they struggle the man shoots McQueen in the shoulder (or perhaps just above the heart) and unlike the novel, in defense McQueen shoots the man, leaving him on the front steps of the mill office as he leaps into the getaway car. Pat (Cyril Cusack) the driver of the getaway car swerves in their escape and McQueen half in and out of the car slides out onto the street and McQueen is left laying prone and unmoving on the street as Pat and the other gang members argue about backing the car up to get him. Finally McQueen slowly gets to his feet and staggers down a side street separating himself from his gang – the odd man out to survive on his own.

Most of the action of Odd Man Out takes place at night and the weather / atmosphere changes from bright sunlight to dark windy night to rain to falling snow almost as though the death that comes with winter is a harbinger of the slow death that McQueen faces as he gets weaker, colder and more lifeless as he encounters or is passed around like a living corpse from one character or set of characters to the next.

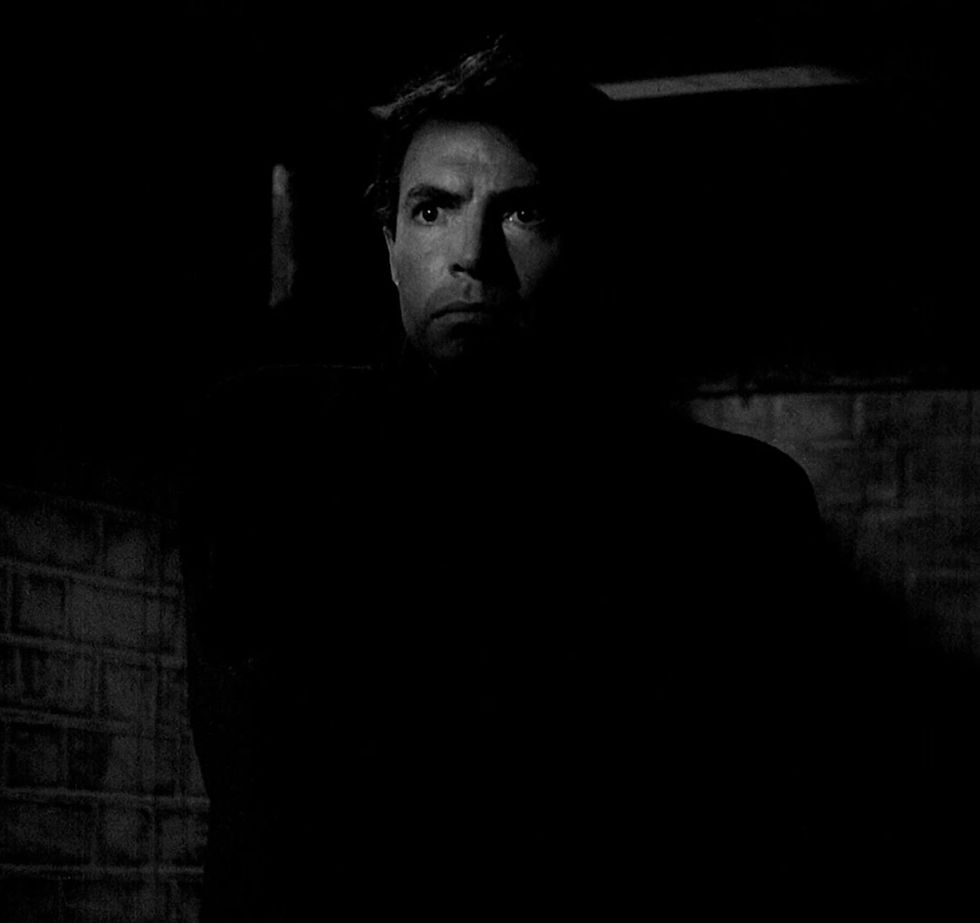

Cinematically, many of the frames of the film are beautifully composed sharp angles of light and shadow, with characters sometimes in silhouette, sometimes partially lit, sometimes set against the decay and debris of a downtrodden urban backstreet, junkyard, alley, or set of row houses – a style that cinematographer Robert Krasker would repeat in The Third Man. Krasker’s scenes and compositions are as visually stunning as any of the work coming out of Hollywood before, during and after this period. Even with the sound turned down, it would be easy to understand the action of the film because the visuals are so strong. As a technical note, the Criterion Collection Blu-ray is a digitally scanned and then cleaned restoration from a composite fine grain 35 mm print from an archived nitrate negative of the film. The result is incredibly sharp, high definition detail throughout.

Reed uses Green’s story as a springboard to explore and examine how other characters react when they encounter the mortally wounded McQueen challenging the viewer to reflect how he or she might respond if put in the same situation. Odd Man Out explores justice, right action, murder, suicide, loyalty, deceit, betrayal, survival, indifference and callousness in situations that increasingly become more extreme and often visually surreal. The wild, eccentric painter Lukey’s (Robert Newton) oddly, distorted cavernous apartment is almost Salvador Dali-esque as McQueen, propped up in a chair stares into it and begins to hallucinate.

Like many of Hitchcock’s characters who are compelled to act unlawfully, unethically or sinfully before they can be redeemed, forgiven or shown innocent, Reed isn’t quick to condemn Johnny McQueen, despite his criminal act or quick to condemn the other characters that encounter him. Reed often lets the viewer experience McQueen’s anguish and dilemma through the character’s eyes as well as the absurdities and mayhem that swirl around him. During the course of the film, the wounded and growing weaker McQueen asks several characters he encounters, who have by this time have heard of the robbery and the shooting, whether the man he shot during the robbery had died and each character ignores the question leaving McQueen at a loss to know whether he has killed or not, even though the audience knows that he had. From a Christian/Catholic viewer’s perspective, McQueen needs to, and near the end of the film, wants to confess his sins as he feels his life slipping away from him but he’s cheated from knowing exactly what the extent of his transgression is. One of the more powerful and unsettling aspects of the film.

Are there possible, if subtle, Catholic allusions in the film? I wouldn’t be the first to comment on them. For example, one might consider McQueen’s long, protracted struggle akin to Christ’s passion. His first hideout is a bomb shelter that is visually reminiscent of a tomb from which he eventually emerges; after his emergence two women take him into their home and care for him; his muted relationship with IRA fellow conspirator Kathleen Sullivan (Kathleen Ryan) is more one-sided as she cares deeply almost reverentially about McQueen while he is more distant and less romantically inclined; and McQueen is considered by another character worthy to turn over to the authorities for a thousand Pounds. Or one can take these situations and characterizations at face value.

Despite the dark subject matter, Reed injects several touches of humor and more raucous action (as he does in The Third Man), so the film doesn’t sink under the weight of the heavy human existential struggle being played out. McQueen is a victim of his own notoriety because many characters tempted to bring him to justice by turning him in to the police whether for the reward money or not know that they would risk retribution from the IRA and so quickly get rid of him or pass him off to others. The film is a fascinating study of human behavior in extreme situations. McQueen is often the catalyst for misguided, wrong, brutal, greedy, or tender, sympathetic and altruistic behavior and sometimes combinations of those from the same character. In that, the film constantly surprises the viewer with characters that are more realistically human rather than one-dimensional stereotypes as in so many of today’s films.

Even though The Third Man is considered Carol Reed’s masterpiece (and it is thoroughly enjoyable – particularly for Orson Welles’ Ferris wheel speech), Odd Man Out was Reed’s personal favorite. After seeing it, it’s easy to understand why. It’s a film that’s rich visually and rich in colorful and often conflicted characters and I’m sure I’ll be watching it several more times to explore it further.

Originally published on Ricochet.com

Comments